DonAK

President of FC Barcelona

Thought this was a good, interesting article by Sid Lowe worth sharing

Link: http://www.theguardian.com/football...na-coaching-champions-league?CMP=share_btn_tw

Barcelona’s winning philosophy makes them coaching incubator for top clubs

Barça’s ideas have been spread across Europe by former players who switched to the dugout, including coaches of four Champions League quarter-finalists

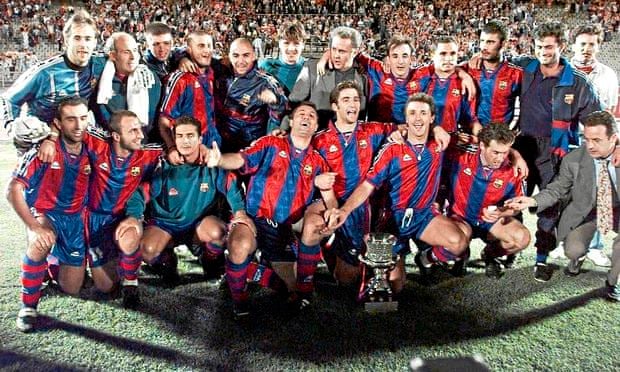

Barcelona celebrate winning the Spanish Super Cup in 1996. Photograph: Marca/Offside

Where are they now? In the dugout, that’s where, and not just any dugout. Take a look at the picture above. It is nearly 19 years old now: 28 August 1996, the side that won the Spanish Super Cup. You will recognise some of the faces, and among them are four of the eight coaches in the Champions League quarter-finals: this week Pep Guardiola’s Bayern Munich face Julen Lopetegui’s Porto and Laurent Blanc’s Paris Saint-Germain take on Luis Enrique’s Barcelona. Their Barcelona, where they all played together.

If it is extraordinary enough that one team provides half the managers left in the competition, go a little deeper. The starting XI that day ran: Lopetegui, Ferrer, Popescu, Abelardo, Blanc, Luis Enrique, Sergi, Amor, Guardiola, Stoichkov, Pizzi. Only two of them have not become first-team coaches: Guillermo Amor, who ran Barcelona’s academy and is now technical director at Adelaide United, and Gica Popescu, sent to jail for three years for fraud. Now there’s a “Where Are They Now?”.

There were 27 players in Barcelona’s squad in the 1996-97 season. Popescu apart, only five others have not worked as coaches or technical directors and among them are Giovanni, who scouts for Olympiakos, and Vítor Baía, an ambassador for Porto, plus the owner of the Fort Lauderdale Strikers, Ronaldo, and another Ballon d’Or winner, the Fifa presidential candidate Luís Figo.

Sergi Barjuan has just taken over at Almería, Juan Antonio Pizzi manages León in Mexico having coached Valencia last season and Chapi Ferrer began this year at Córdoba, while Albert Celades is Spain’s Under-21 coach, Emmanuel Amunike coaches Nigeria’s Under-17s and Roberto Prosinecki manages Azerbaijan, to name but a few. Barça’s manager when they won the Super Cup, the Copa del Rey and the Cup Winners’ Cup was Sir Bobby Robson. Oh, and you might recognise his assistant, too: José Mourinho.

“Surprised? Not at all. The best club in the world, surrounded by the best players, learning from the best coaches. Why should I be surprised?” asks Hristo Stoichkov, who has coached Celta and Bulgaria.

Perhaps because others are. On Wednesday Luis Enrique faced his friend Sergi at the Camp Nou. Asked afterwards if the pair looked like being coaches back then, he laughed: “We looked like anything but coaches.” But, Luis Enrique added, “things change”. They change for everyone and fate isn’t entirely random. The length of the list invites the conclusion that Barcelona were conditioning them, forming managers even if they did not know it.

Luis Enrique, Sergi, Guardiola and Abelardo Fernández were especially close, the gang of four. Abelardo coaches Sporting Gijón. “I got my badge at 27, 28. I wasn’t thinking: ‘I’ll coach’, it was more a ‘just in case,’” he says. “Later you think about coaching and your experiences at Barcelona – and in my case Sporting – contribute but I wouldn’t necessarily have bet on those four, or any of us.”

Abelardo continues: “The only one out of the ordinary was Pep. He’d study videos carefully and showed an excessive interest in technical and tactical questions for a player.”

Others also noticed something about Guardiola. “Pep would participate, discuss, talk constantly, order,” Amor says of the midfielder whom Bobby Robson would recall as “always ready to speak his mind”. “You could tell with Pep, the reference point,” agrees Stoichkov. Óscar García, a member of that Barcelona squad who later coached Brighton and Watford, says: “Pep was the one.”

The one, but not the only one. The players had already identified Mourinho as different – “as a tandem he and Bobby were among the best”, Stoichkov says – while he in turn identified Guardiola, Luis Enrique and Blanc as the players most interested in the game’s mechanisms, spending time studying his technical reports. Blanc said he and Mourinho had “good discussions”: “Even then I was passionate about tactics.”

“They were all strong personalities, knowledgeable technically and tactically,” says Abelardo. He describes Lopetegui as preparado; diligent, qualified, intelligent. Amor describes Blanc as “a señor in every sense: well-mannered, intelligent, serious”. García describes Luis Enrique as “methodical, strict, with a real desire to win”.

Others were emerging too. There’s no catch-all explanation, no single reason for so many coaches emerging from that team, still less reaching such a high level, but players were being shaped by their environment, developing the personality, interest and knowledge to manage. The desire to manage, too. It wasn’t always positive, but bad times taught too: “You learned to live with pressure,” García says of a season that was a case study in the club’s self-destructive entorno, its political, social and media environment.

In some cases those shared experiences helped them become a certain type of manager, in style and methodology. “Barcelona’s game is based on attacking, possession, winning. If you look at [those coaches], many have the same idea,” Amor says.

When Zlatan Ibrahimovic dismissed Guardiola as a “philosopher”, it was an attack, but he does have a philosophy. Blanc may not always have practised what he preaches but during Euro 2012 he said: “Watching Spain is a pleasure. Their philosophy is one I love and know; it’s Barcelona’s philosophy.” Lopetegui arrived at Porto via the Spanish national team youth structure, bringing a technical, possession game in a 4-3-3 formation. “They wanted a specific way of playing,” he says.

Curiously, of the four some might argue the least “Barça” is the one at Barça. Results have been superb but the debate is often ideological, focused on the style under Luis Enrique. Yet his deviation has been exaggerated and he has been shaped by similar ideals, beginning at Barcelona B while Guardiola was first-team coach and Amor academy director.

Here, Johan Cruyff, in charge from 1988 to the spring of 1996, is an important figure. Stoichkov recalls: “I’d never tell a player: ‘Do what I did.’ That was one of Johan’s lessons that really stayed with me. It’s too much pressure. You can correct, help, guide, but don’t say that, never, ever.” But it was less about specific lessons, more about ideas – encapsulated by Txiki Begiristain, who played for Barcelona until 1995. “Every time Cruyff needed a solution, he attacked more.”

That influenced their managerial style and philosophy; it also influenced their career path. It was not just about making players coaches but about making players want to be coaches. Asked to explain the proliferation, Amor says: “Johan has a part to play, for sure.” He says: “There’s something basic, beyond results: the fact that we enjoyed it so much. The ideas carry you. When you enjoy something it’s lovely, so you want to keep going when your playing career ends.”

García, whose first coaching job was as Cruyff’s assistant with the Catalan national team, has a similar view: “You feel like teaching, passing on what you learned and enjoyed. You’re not conscious before, but maybe a process had started. Cruyff’s way was different, about the why? Not just doing things, understanding them. I’m proudest when my players say they’ve learnt something; that satisfies more than titles.”

Lopetegui insists: “I want players to really understand the game,” and Mourinho recalled a squad for whom it was not enough for the coach to be right, he had to demonstrate he was right.

There is a contradiction here which Abelardo quickly highlights: in 1996-97, Cruyff was not the coach, Robson was. And while Stoichkov notes that Luis Enrique and Blanc were signed by the Dutchman, they never played under him. Much of the culture remained, though, and Robson was a different lesson, variety. Popular, he won them over by his personality and his management of theirs. He did not just tell, he listened.

More than that, players admit that in 1996-97 there was a degree of auto-gestión, self-management, which may even have helped develop coaches. Mourinho stepped forward, Stoichkov describing him as “the typical guy who likes to be on top of everything: I learnt a lot from him, he was different.” And the players stepped forward too. “We took on a lot of responsibility,” Amor says.

Abelardo is not convinced while Stoichkov will not hear a word said against Robson, of whom he is fond, but Óscar says: “Maybe that autogestión is a factor. Without realising it, perhaps that forms leaders, people thinking about the game.”

Stoichkov says: “Pep, Luis Enrique, Laurent, Julen … I’m not surprised. They always had talent and personality plus good people around them. We were at the world’s best club and when you get used to winning you want to keep going.”

Amor adds: “It’s lovely to see four team-mates, people you’ve been fortunate to play with, in the quarter-finals. Hopefully we’ll see one of them win the final too.”

Link: http://www.theguardian.com/football...na-coaching-champions-league?CMP=share_btn_tw

Barcelona’s winning philosophy makes them coaching incubator for top clubs

Barça’s ideas have been spread across Europe by former players who switched to the dugout, including coaches of four Champions League quarter-finalists

Barcelona celebrate winning the Spanish Super Cup in 1996. Photograph: Marca/Offside

Where are they now? In the dugout, that’s where, and not just any dugout. Take a look at the picture above. It is nearly 19 years old now: 28 August 1996, the side that won the Spanish Super Cup. You will recognise some of the faces, and among them are four of the eight coaches in the Champions League quarter-finals: this week Pep Guardiola’s Bayern Munich face Julen Lopetegui’s Porto and Laurent Blanc’s Paris Saint-Germain take on Luis Enrique’s Barcelona. Their Barcelona, where they all played together.

If it is extraordinary enough that one team provides half the managers left in the competition, go a little deeper. The starting XI that day ran: Lopetegui, Ferrer, Popescu, Abelardo, Blanc, Luis Enrique, Sergi, Amor, Guardiola, Stoichkov, Pizzi. Only two of them have not become first-team coaches: Guillermo Amor, who ran Barcelona’s academy and is now technical director at Adelaide United, and Gica Popescu, sent to jail for three years for fraud. Now there’s a “Where Are They Now?”.

There were 27 players in Barcelona’s squad in the 1996-97 season. Popescu apart, only five others have not worked as coaches or technical directors and among them are Giovanni, who scouts for Olympiakos, and Vítor Baía, an ambassador for Porto, plus the owner of the Fort Lauderdale Strikers, Ronaldo, and another Ballon d’Or winner, the Fifa presidential candidate Luís Figo.

Sergi Barjuan has just taken over at Almería, Juan Antonio Pizzi manages León in Mexico having coached Valencia last season and Chapi Ferrer began this year at Córdoba, while Albert Celades is Spain’s Under-21 coach, Emmanuel Amunike coaches Nigeria’s Under-17s and Roberto Prosinecki manages Azerbaijan, to name but a few. Barça’s manager when they won the Super Cup, the Copa del Rey and the Cup Winners’ Cup was Sir Bobby Robson. Oh, and you might recognise his assistant, too: José Mourinho.

“Surprised? Not at all. The best club in the world, surrounded by the best players, learning from the best coaches. Why should I be surprised?” asks Hristo Stoichkov, who has coached Celta and Bulgaria.

Perhaps because others are. On Wednesday Luis Enrique faced his friend Sergi at the Camp Nou. Asked afterwards if the pair looked like being coaches back then, he laughed: “We looked like anything but coaches.” But, Luis Enrique added, “things change”. They change for everyone and fate isn’t entirely random. The length of the list invites the conclusion that Barcelona were conditioning them, forming managers even if they did not know it.

Luis Enrique, Sergi, Guardiola and Abelardo Fernández were especially close, the gang of four. Abelardo coaches Sporting Gijón. “I got my badge at 27, 28. I wasn’t thinking: ‘I’ll coach’, it was more a ‘just in case,’” he says. “Later you think about coaching and your experiences at Barcelona – and in my case Sporting – contribute but I wouldn’t necessarily have bet on those four, or any of us.”

Abelardo continues: “The only one out of the ordinary was Pep. He’d study videos carefully and showed an excessive interest in technical and tactical questions for a player.”

Others also noticed something about Guardiola. “Pep would participate, discuss, talk constantly, order,” Amor says of the midfielder whom Bobby Robson would recall as “always ready to speak his mind”. “You could tell with Pep, the reference point,” agrees Stoichkov. Óscar García, a member of that Barcelona squad who later coached Brighton and Watford, says: “Pep was the one.”

The one, but not the only one. The players had already identified Mourinho as different – “as a tandem he and Bobby were among the best”, Stoichkov says – while he in turn identified Guardiola, Luis Enrique and Blanc as the players most interested in the game’s mechanisms, spending time studying his technical reports. Blanc said he and Mourinho had “good discussions”: “Even then I was passionate about tactics.”

“They were all strong personalities, knowledgeable technically and tactically,” says Abelardo. He describes Lopetegui as preparado; diligent, qualified, intelligent. Amor describes Blanc as “a señor in every sense: well-mannered, intelligent, serious”. García describes Luis Enrique as “methodical, strict, with a real desire to win”.

Others were emerging too. There’s no catch-all explanation, no single reason for so many coaches emerging from that team, still less reaching such a high level, but players were being shaped by their environment, developing the personality, interest and knowledge to manage. The desire to manage, too. It wasn’t always positive, but bad times taught too: “You learned to live with pressure,” García says of a season that was a case study in the club’s self-destructive entorno, its political, social and media environment.

In some cases those shared experiences helped them become a certain type of manager, in style and methodology. “Barcelona’s game is based on attacking, possession, winning. If you look at [those coaches], many have the same idea,” Amor says.

When Zlatan Ibrahimovic dismissed Guardiola as a “philosopher”, it was an attack, but he does have a philosophy. Blanc may not always have practised what he preaches but during Euro 2012 he said: “Watching Spain is a pleasure. Their philosophy is one I love and know; it’s Barcelona’s philosophy.” Lopetegui arrived at Porto via the Spanish national team youth structure, bringing a technical, possession game in a 4-3-3 formation. “They wanted a specific way of playing,” he says.

Curiously, of the four some might argue the least “Barça” is the one at Barça. Results have been superb but the debate is often ideological, focused on the style under Luis Enrique. Yet his deviation has been exaggerated and he has been shaped by similar ideals, beginning at Barcelona B while Guardiola was first-team coach and Amor academy director.

Here, Johan Cruyff, in charge from 1988 to the spring of 1996, is an important figure. Stoichkov recalls: “I’d never tell a player: ‘Do what I did.’ That was one of Johan’s lessons that really stayed with me. It’s too much pressure. You can correct, help, guide, but don’t say that, never, ever.” But it was less about specific lessons, more about ideas – encapsulated by Txiki Begiristain, who played for Barcelona until 1995. “Every time Cruyff needed a solution, he attacked more.”

That influenced their managerial style and philosophy; it also influenced their career path. It was not just about making players coaches but about making players want to be coaches. Asked to explain the proliferation, Amor says: “Johan has a part to play, for sure.” He says: “There’s something basic, beyond results: the fact that we enjoyed it so much. The ideas carry you. When you enjoy something it’s lovely, so you want to keep going when your playing career ends.”

García, whose first coaching job was as Cruyff’s assistant with the Catalan national team, has a similar view: “You feel like teaching, passing on what you learned and enjoyed. You’re not conscious before, but maybe a process had started. Cruyff’s way was different, about the why? Not just doing things, understanding them. I’m proudest when my players say they’ve learnt something; that satisfies more than titles.”

Lopetegui insists: “I want players to really understand the game,” and Mourinho recalled a squad for whom it was not enough for the coach to be right, he had to demonstrate he was right.

There is a contradiction here which Abelardo quickly highlights: in 1996-97, Cruyff was not the coach, Robson was. And while Stoichkov notes that Luis Enrique and Blanc were signed by the Dutchman, they never played under him. Much of the culture remained, though, and Robson was a different lesson, variety. Popular, he won them over by his personality and his management of theirs. He did not just tell, he listened.

More than that, players admit that in 1996-97 there was a degree of auto-gestión, self-management, which may even have helped develop coaches. Mourinho stepped forward, Stoichkov describing him as “the typical guy who likes to be on top of everything: I learnt a lot from him, he was different.” And the players stepped forward too. “We took on a lot of responsibility,” Amor says.

Abelardo is not convinced while Stoichkov will not hear a word said against Robson, of whom he is fond, but Óscar says: “Maybe that autogestión is a factor. Without realising it, perhaps that forms leaders, people thinking about the game.”

Stoichkov says: “Pep, Luis Enrique, Laurent, Julen … I’m not surprised. They always had talent and personality plus good people around them. We were at the world’s best club and when you get used to winning you want to keep going.”

Amor adds: “It’s lovely to see four team-mates, people you’ve been fortunate to play with, in the quarter-finals. Hopefully we’ll see one of them win the final too.”